Age Related Loss of Muscle-How Can we Stop This?

- 21st Oct 2022

- Read time: 26 minutes

- Dr. Max Gowland

- Article

We are all interested in our health and longevity. This becomes even more top of mind as we age. But did you realise that your muscle mass and muscle quality can actually determine your longevity. This sounds incredible, I know, but there are many published scientific peer reviewed papers proving the association of muscle mass in both males and females, with the risk of death.

Over the last few decades, we have been living longer and longer with average female life expectancy touching 83 years, with males reaching just below 80 years.

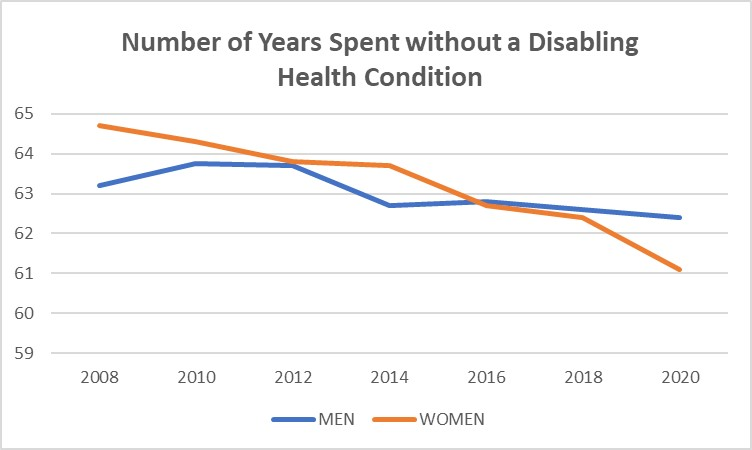

More recently life expectancy has failed to improve further and what is more worrying is that a recent ONS survey shows that between 2006 and 2020 disability-free life expectancy has actually fallen by four years on average. This is not good news and shows that whilst life expectancy is moving up, the actual number of years spent in full health has decreased.

Optimal longevity would be to increase life span, but simultaneously reduce the number of years spent in ill health too. That is the ideal. After all, this is what prevention is all about. Why wait until we are sick before we do something about our health? We all know that prevention is so much better than cure, yet most of us do little to prevent chronic disease, until it’s too late. Prevention will also increase our quality of life too.

It is well accepted that staying active is essential to a long and healthy life. This regular activity combined with good nutrition and good sleep is the ‘secret’ to optimal longevity.

But there is now growing and well accepted science showing that muscle mass and strength are associated with longer life. In fact, some would say that this may even be the most important determining factor.

Loss of muscle mass starts in our forties and accelerates as we age, with between 1-3% loss of muscle each year. In fact, losing muscle and strength is the greatest cause of functional decline and ultimate frailty. Muscle is VERY, VERY important and tends to be forgotten by many health professionals as a key metric when it comes to measuring one’s overall health and vitality.

Let’s Understand Muscle First

We have 650 muscles in our body of which there are three distinct types.

The majority of our muscle is ‘skeletal muscle’ which is attached to bones being responsible for our movement. Then there is ‘smooth muscle’ such as that within blood vessels, GI tract, bladder and uterus. Finally, there is the specialised ‘cardiac muscle’. However, though there are these three types of muscle, the basic muscle fibre and its make up is the same. As you can see from the illustration, the muscle is rather like strands of rope, consisting of intertwined mini ropes, with they themselves also being made of even smaller fibres, which gives the muscle its overall strength and robustness.

Basically, muscle receives signals from our motor neurons, which messages the muscle to either contract or relax. In turn muscles are ‘innervated’ which means that they can receive these signals effectively and contract accordingly.

Muscle is Largely Composed of Protein

The major component of muscle is water (75%), with the next largest being protein itself. Muscle also contains a certain amount of fat, though this varies from between 1 to 10%, depending on muscle age and metabolic health. Finally, glycogen (which is a polymer of glucose) is housed within our muscle(ca. 1%) and plays a key role in glucose uptake after a meal.

Before we talk about the mechanisms of muscle loss with age, it’s important to just have a basic understanding of what comprises protein itself.

The basic building blocks of proteins are ‘amino acids’ (AAs). All these AA’s have the same basic structure but vary in their side chains which have twenty different variations, all of which play a different part in our metabolism. These AA’s join together chemically to form longer chains called peptides, with can extend further to then become proteins. These protein molecules then become folded to produce the final finished structured protein.

Without protein, there is no life, so this macronutrient is by far the most important. Protein is used not only in muscle, but also to form collagen rich tissues such as skin and cartilage. It is also metabolised into bone matrix, into the essential oxygen-carrying haemoglobin and a whole host of various enzymes and hormones. Finally, protein is used to repair cells all over the body.

Muscles are constantly being turned over following daily muscle fibre damage, which in turn is then repaired by new protein from the diet. Muscle turnover has been measured at around 6g per kg per day, which means that in a 70kg person, around half a kilo of muscle is being replenished every single day. If the rate of protein loss via breakdown is not at least matched by new protein synthesis, then muscle tissue is lost. A certain amount of muscle tension or ‘resistance’ is needed daily to constantly stimulate the muscle, which if absent(as with sedentary behaviour) will lead to muscle loss.

Age Related Loss of Muscle (Sarcopenia)

After the age of around forty, both males and females tend to start losing muscle mass, tone and strength. This is a natural part of ageing. Typically, this can vary, depending on the amount of activity of that person, but typically this is around 1% per year, which then accelerates to around 3% for older individuals in their 70s and beyond.

Let’s look at what this muscle loss actually looks like in an MRI scan of both young and older adults:

In the 21-year-old, the muscle (grey) is large, with little fat mass(the outer white), whilst the 63 year old has a significantly reduced amount of muscle, together with reduced quality of muscle too. There is considerable ingress of fat into the muscle which is typical of an older adult. This is classical age-related loss of muscle or ‘sarcopenia’. It is not a disease but simply one facet of ageing, but one which is very important, as muscle mass is associated with longevity, and losing too much muscle mass has been proved to be unhealthy.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. If you exercise regularly, for example pumping some iron in the gym or simply doing other forms of ‘resistance’ exercise, then it is entirely possible to slow down this sarcopenia, or even reverse it to some extent, as can be seen by the MRI scans below.

But Why Does Muscle Decay with Age

The well know maxim ‘Use it or Lose it’ certainly applies to sarcopenia and how sedentary behaviour can speed up this muscle ageing process. But what actually causes muscle to degrade?

It is a multi-faceted set of processes, with no particular mechanism being responsible on its own, though lack of use is certainly a key factor. A decline in the well-known anabolic androgen hormones is a large factor too, where testosterone levels decline in both males and females over time. There tends to be increased inflammation too in ageing adults, which again just adds to the muscle destruction process. The so called ‘fast twitch’, type 2 fibres also decline rapidly, causing yet more muscle loss and also a loss in balance and strength. Muscles contain small organelles called ‘mitochondria’ which are the energy producing centres of the cell and they too undergo both destruction but also decline if their effectiveness.

One other theory points to the fact that the amino acids(the building blocks of protein and therefore muscle) are less available to muscle tissues due to what the scientists call ‘splanchnic extraction’, which means that these AA’s are absorbed and removed from potential protein synthesis by other organs such as the liver. This extraction is known to increase in older adults making protein synthesis, and therefore muscle maintenance, that much more difficult.

Older adults need to work harder in the gym than younger adults if they wish to retain muscle mass. Ensuring adequate protein intake (more about this later) is crucial as is regular resistance exercise, but this anabolic resistance tends to worsen with age, so considerable effort is needed to simply hold on to valuable and healthy muscle.

How Does Muscle Loss make us Unhealthy

Though many of the scientific studies are ‘association’ studies which don’t necessarily prove causality, nevertheless, muscle loss is associated with many areas of health decline. General cellular senescence (cell growth arrest or slow down) is a well-known cell phenomenon, where some of these cells instead of dying (apoptosis), become ‘sick’ and refuse to die. Some call these ‘zombie’ cells and it is these zombie cells which can end up producing highly inflammatory biochemicals which can lead to poor health and even cancers later in life. Inflammation is a known cause of many chronic diseases and also is a process which can cause loss of muscle tissue.

Ageing muscle contains reduced levels of failing mitochondria(the energy centres of the cell), and muscle being so energy intensive, is significantly affected when mitochondria die or are reduced in their efficiency.

Loss of muscle is also associated with low vitamin D status. Vitamin D is essential for muscle function and low levels are known to cause muscle weakness and even issues with balance too. Sarcopenia is also associated with another wasting disease which is the loss of bone, better known as osteoporosis. But it doesn’t stop here, as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and even COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) is also found in older adults who have lower muscle mass than average.

Clearly there is a decline after the age of around 40 years, but the steepness of this downward trajectory can be affected by so many factors, most of which are certainly within our control. Eventually you can cross the ‘disability threshold’ far too early in life and with the right lifestyle it could have been so easy to avoid.

What can cause even greater issues and speed up decline further is what we call a ‘catabolic crisis’.

This is an event, such as a hip operation, where extended periods of time are spent at rest with little or no muscle stimulation. So, you can imagine that you are already on the muscle mass decline and suddenly, you are confronted by this period of bed rest. This will cause a larger loss of muscle mass, and overall function, which is always so difficult to claw back, even with exercise, unless there is considerable determination. When a series of such catabolic crises occurs, there can then be considerable loss of functionality, leading ultimately to earlier than average frailty.

Falls Can be Catastrophic

When you are young, falling is very seldom a problem. You simply get up, dust yourself off and laugh about it afterwards. It is quite different when you fall if you are say, over 60 years old.

In fact, one in three older adults suffer a serious fall every year and some of these falls will lead to life changing events and even death. In the UK alone, there will be around 100,000 hip fractures mainly as a result of the combination of a fall and weakened osteoporotic bone. Recovery from a hip operation can be slow in older adults, as confidence is lost and is only gradually restored over time. Some but not all hip fracture patients will go on to recover their full function with time providing they put in the required effort, not only during rehab, but also when they are on their own and discharged from the physio. But published studies show that this is disappointingly only around 25%.

However, nearly thirty percent of hip fracture patients will die within twelve months. This is a surprising and quite frightening statistic to most readers, though orthopaedic surgeons will be well aware of this stat.

However, one piece of positive news is that even nonagenarians can still build muscle mass, they can build strength and also improve their gait, all of which will be associated with quality of life and longevity. It is never too late and again, our speed of recovery and our general health is within our own control.

How to Combat Age Related Muscle Loss (Sarcopenia)

The most potent way to inhibit sarcopenia is regular resistance exercise. Preferably a gym with the appropriate machines is best of course, but there are also so many ways to achieve resistance exercise without the need to visit a gym. Any personal trainer will be able to help anyone to carry out these exercises at home,but there is also so much available on the net where body weight exercises are infinite in their ability to stress every single aspect of virtually all our skeletal muscles.

But what is less well understood is the effect of diet on muscle loss and also muscle growth in older adults. As you might expect, protein is the key macro in your diet and there is a huge amount of scientific data showing clearly that low protein intake is a recipe for muscle loss, especially as we age.

Look at the graphic below for example.

This is a very well-known longitudinal study where over 2000 older adults were followed over three years, with a detailed understanding of their dietary intake using food diaries. These people also had their muscle mass measured using a tool called a DEXA (which stands for dual energy x -ray absorption). DEXA is seen as the gold standard for measuring lean body mass so this study is both high quality and representative of reality, rather than some artificial in-lab experiment.

The data shows quite clearly that those people who had the lowest protein diets lost most muscle mass, even measurable within this fairly short three year period, and those who ate higher protein diets were better able to retain their all-important muscle mass over the same period.

So, clearly eating a higher protein diet is, perhaps obviously, a way of slowing down sarcopenia. But what does ‘higher protein diet’ actually mean? And how much protein should older adults be eating in their diet?

How Much Protein do we Need to Eat

In Europe and the US for example, the RDA (recommended daily intake) for protein is 0.8g per kg of body weight daily. This means that for a 75 kg person, protein intake is suggested to be a minimum of 60g daily. These RDA’s were set many years ago and much of this RDA setting was calculated using what are called nitrogen balance studies where technicians measure nitrogen(which is a marker for protein) intake in the diet vs nitrogen excretion. However, more recent studies have tended to focus more of the measurement of actual muscle mass, making these trials much more realistic than the more theoretical nitrogen studies.

It is now generally accepted by world class scientists that the old RDA of 0.8g/kg/d is out of date and should be raised to at least 1.0 -1.2g per kg/day. Some scientists argue that even this additional 50% increase in RDA is not enough and many suggest up to 1.5g/kg/d for older adults. There will clearly be ongoing debate as to the exact RDA target, but one thing is sure, and that is that older adults do in fact need to increase their intake of protein generally, as most are way short of this new RDA.

A recent 2017 study of what older adults are actually consuming in the UK shows very clearly that around 80% are failing to achieve the 1.2g/kg/d and this means that they will be more prone to losing valuable muscle mass as they age further. These data come from highly trusted sources such as the Public Health England (PHE) National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS). Another study recently cited by a well know scientist, Professor Paddon-Jones, backs this up further by citing US data (from their own diet studies, namely the NHANES study) which shows that over a third of US adults over 50 yrs fail to reach even the out of date 0.8g/kg/d. Both these studies clearly show that generally speaking, older adults are failing to eat the optimal amount of protein in their diets, which in turn will simply give rise to a more rapid loss of muscle mass as they age. Few realise this too!

One of the largest studies ever commissioned on protein requirements (the Prot Age Study) was recently published in the scientific press and concludes also that older adults should be eating more protein generally, between 1.0-1.2g kg/day minimum, but if suffering from a chronic disease, or recovering from an operation, this should increase further to 1.5g as this is when the body is crying out for protein to help rebuild itself and help with cell turnover.

But eating between 1.2-1.4 g/kg/d is not always a simple and achievable target, in fact quite the contrary. This is the equivalent of a 75 kg person having to eat around 100 grams of protein each day which sounds easy enough but in real food terms, this is the equivalent of eating four chicken breasts, or if you prefer, eighteen eggs! Neither of these is achievable for most people.

Admittedly, other protein sources should be counted, but a few grams in bread plus a few grams in vegetables tends to be a low-grade protein source, so reaching the 100 grams is not always that easy. This is why protein supplementation should be seriously considered to help make up that missing protein deficit. A high-quality protein drink can also act a vehicle to add further essential supplemental micronutrients too such as vitamin D, calcium and zinc, all of which play a key role in muscle function.

What is the Best protein for Retaining Muscle Mass

The most important thing is to simply ensure you get that essential 100 grams of protein each day, no matter what source. This is by far the most important objective in order to hold on to muscle mass. However, all proteins are not created equal with some having the edge over others when it comes to muscle mass.

If you go back to the previous information on the make-up of protein, there are the basic two types, namely the non-essential amino acids and the essential amino acids(AAs). It is well accepted that sources of protein with the higher levels of the essential AAs have a better AA profile than those with lower essential AA content. Furthermore, of these so-called essential AAs, there are three particularly important AA’s. These are the ‘branched chain amino acids’ (BCAAs) which are leucine, iso-leucine and valine. Leucine in particular, seems to be top of the pack as again, science has proven that leucine is by far the most anabolic of all the AAs found in protein as it ‘turns on’ the muscle protein synthesis mechanism. There are also plenty of studies showing that leucine can also slow down the loss of muscle in seniors and therefore leucine content in protein is associated with greater muscle mass protection.

Animal vs Plant Protein-Which is Best?

This tends to be an ongoing debate between the pro-plant lobby and the omnivore lobby, which is usually based more on Twitter feeds than real science! In nutrition, there can sometimes be a pseudo-religious following of certain diets and beliefs which can snowball into social media rows with little of no substance. This area is one of those classics which attracts such debates.

Let me try and clarify. We know for sure that we need to stimulate muscle protein synthesis (MPS) and we also know that this is best done by the essential AAs, especially the BCAAs and also leucine itself as the ‘master’ amino acid MPS catalyst. There are countless studies which have proved this in human clinical trials. Also, animal sources of protein are far more concentrated than those derived from plant sources. For example, animal proteins will typically give you around 20-30% of protein by weight, while plant based sources can vary between 3-12% only, making it more difficult to get that 100 grams per day, as discussed above. But plant sources also have some advantages such as a source of fibre.

Is Protein Safe for Bones and Kidney Health?

The answer is a simple one. Yes, for bones and, generally yes, for kidney health.

Firstly, on bone health and osteoporosis, some believe that protein causes an increase in the acidity of blood plasma which is capable of ‘dissolving’ bone tissue. Yet in reality the body operates what is called ‘homeostasis’ which is the body’s ability to carefully maintain a very slight alkalinity in the blood, between 7.36-7.44, which is an extremely narrow and closely controlled pH spectrum. This theory fails to account for the function of our kidneys which produce alkaline bicarbonate ions that neutralise any acidity in blood plasma, hence ensuring that our blood plasma remains within this carefully critically important pH spectrum.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) states that protein additionally exerts a direct anabolic effect on the bone matrix. WHO also states that a low protein diet will lead to loss in bone over time. They conclude that ‘dietary protein is most likely beneficial for bone, even in excess of recommended intake’. Another highly influential organisation, the UK’s National Osteoporosis Society, also conclude that higher protein diets are perfectly safe, in fact these diets even exerted a positive trend for bone mineral density (BMD) across their cited studies.

Within the social media world and many health magazines, again there is a myth that protein is bad for our kidneys. Higher protein diets therefore are frowned upon by some, despite the benefit on muscle mass and function for older adults. In a recent meta-analysis, it was concluded that there was no difference in the efficiency of kidney function over time, as measured by changes in GFR (glomerular filtration rate). In the well-known Nurses Health cohort study, again high protein intakes were not associated with any changes in GFR in those women with normal renal function. In the multi-university study, namely the The Prot Age study, it also concluded that those adults who have either acute or chronic disease require more protein than the RDA. This study did add however that those with severe kidney disease are an exception to this rule and should limit protein intake.

Can Other Nutrients Help Besides Protein?

Omega 3:

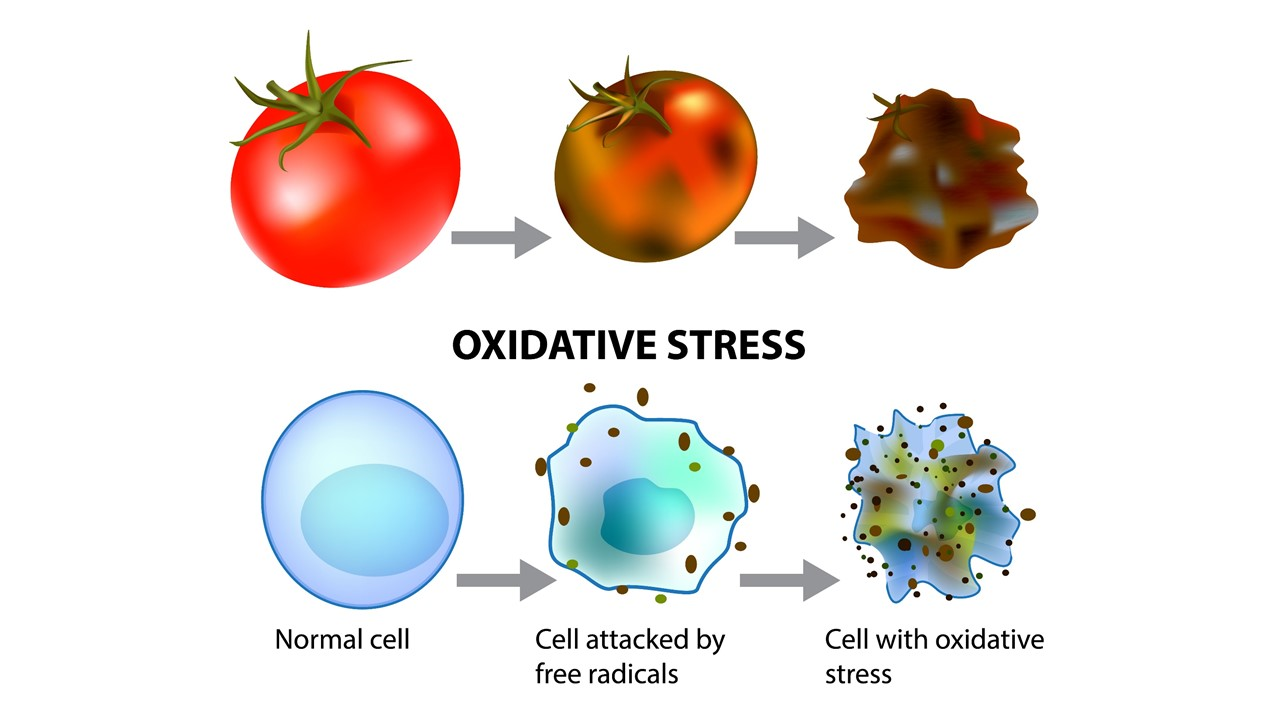

One of the issues with ageing is a continual attack by highly reactive oxygen species or free radicals (ROS) on almost every tissue type. This causes general inflammation and is destructive also to muscle tissue. One of the most studied anti-inflammatory nutrients is the long chain polyunsaturated omega-3 fats such as DHA and EPA, that are available from oily fish. The other well known omega-3 is ALA but this is not converted to the much more nutritious DHA/EPA omega 3’s.

A recent systematic review published in 2021, where 123 studies were reviewed together in a meta-analysis, showed that eating diets with higher amounts of DHA/EPA were associated with both higher muscle mass and also a stronger grip strength too. This benefit is most likely due to the damping down of general inflammation, especially within the muscle tissues.

HMB (hydroxy methyl butyrate):

HMB is a metabolite of leucine so perhaps there is no surprise that trials have shown that the regular ingestion of HMB can inhibit the loss of muscle mass in older adults.

This was observed on those people who exercised but also those that did not exercise. In fact, this particular nutrient is used in certain medical foods to help older adults recover from operations and also help build back their strength. The mechanism is believed to be related to the inhibition of protein degradation which clearly will have an effect on muscle mass over time. It is also used with patients with cachexia.

And Micronutrients?

Despite the very low daily requirements of both vitamins and minerals, there is ample evidence that low intakes are associated with more rapid loss of muscle in seniors. We know that data from Public Health England (PHE) evaluated in 2000 and later in 2016, that the vast majority of older adults are failing to reach the RDA on most vitamins and minerals.

Insufficiency in these crucial micronutrients will make these people more prone to a long list of chronic ailments and even disease later in life, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, joints issues and even brain and cognition disorders. Micronutrient insufficiency combined with poorer absorption of nutrients, further combined with the effect of various medications, can all add up to greater and greater vitamin and mineral deficiencies. Many of these missing nutrients will be required for basic muscle function, so getting these via supplementation can be a sensible health insurance policy.

Let’s start with the list of legally approved health claims, as proven via a selection of high calibre scientific trials under the auspices of the European Food Safety Authority, otherwise known as EFSA.

To acquire a health claim for a particular nutrient is extremely difficult, as the scientific standard set by EFSA is just so high. This means that those nutrients with their accompanying scientific health claim dossiers, will have been through a huge amount of interrogation by a panel of scientists making these legal health claims.

Having said this, there are some nutrients that have been through the EFSA process and have been proven to offer health benefits within the area of muscle health and muscle protein synthesis (MPS). Clearly protein is at the top of the list showing both the maintenance of muscle but also the growth of muscle mass too, can be claimed by agreed levels of protein.

Micronutrients that contribute to muscle function directly include calcium, magnesium, potassium and Vitamin D, so these nutrients will be crucial to get into the diet and if not diet, via sensible supplementation, perhaps via a tailored formulation or a multi-vitamin, though the protein will need to be a separate shake style product in order to acquire enough to make a difference.

Folic acid together with zinc has been shown to contribute to the synthesis of amino acids in general, which are after all, the base building blocks of protein. The less well-known molybdenum micronutrient is also needed for the synthesis of sulphur containing amino acids such as cysteine. Hence the importance of a variety of micronutrients too in the muscle maintenance process.

As previously mentioned, muscle is under attack from reactive oxygen species (ROS) ,otherwise known as ‘oxidative stress’ usually in the form of free radicals which can cause havoc with the deterioration of not only muscle cells, but cells across the whole body. This is why various studies have shown that sarcopenic patients with low muscle mass also tend to have low levels of important anti-oxidants like selenium and vitamin E. Other antioxidants such as lycopene, lutein and zeaxanthin have also been found to be very low in those adults with lower muscle mass. These are all from the ‘carotenoid’ family and are usually found in a variety of coloured fruit and veg such as tomatoes, apricots, grapes, cranberries and other highly coloured dark leafy greens.

Staying Active is Key so Fighting Fatigue must also be Addressed

Finally, one of the most important areas to manage as we age is fatigue. A lack of energy will importantly be indirectly related to loss of muscle mass due to an overly sedentary behaviour. In fact, recent research with groups of over 50s showed that lack of energy was the number one complaint and most people would consider virtually anything to try and maintain their energy levels throughout the day. Lack of energy is a precursor to what I call the vicious spiral to frailty.

Being tired means sitting around, which in turn means loss of muscle mass. This then puts greater strain on joints and a whole host of physical complaints can then start. This then means that it is even harder to stay active, which in turn, means we are then less active and this cycle goes round and round. This lack of exercise ,in fact, lack of general movement can lead to frailty far too early in life, and loss of muscle mass and the onset of sarcopenia will simply speed up this process as we age.

This is why staying active is so important, especially as we get that bit older. Again, as cited at the beginning of this blog, exercise is the single most important thing to add to our daily routine and if this can be resistance exercise, then that will be even better for maintaining muscle mass and also strength too.

Diet also plays a key role, as we have seen throughout this article, not only dietary protein but also ensuring that you get enough of all the various micronutrients too. As we age, getting all these key nutrients into our diet at levels which are at the RDA or more, can be difficult according to PHE data as above, so supplementation should be seriously considered. This will also apply to managing fatigue where the B vitamin family, of which there are eight types, play a crucial role in keeping our energy levels high. Many of the minerals too are important for generating energy such as magnesium, iron, iodine, calcium and even copper, all of which have been proven to help fight fatigue. These minerals together with vitamin C form a group of fatigue-fighting micronutrients which must be topped up daily if we are to avoid fatigue throughout the day. As can be seen from the above graph on deficiencies, many of us are simply lacking these and this will in turn be reflected in our energy levels. Of course, we should have a ‘food first’ philosophy, but for many good reasons, as outlined above, this is just not always possible, so again, supplementation should be considered as a way to ensure we have at least the daily target of these important nutrients.

Take Out Summary

Admittedly, this has been a lengthy blog, but is such an important subject and one which tends not to get enough discussion in the popular press. But there is so much to discuss within the field of muscle loss and ageing. Even this blog has had to skim the surface of a much deeper set of scientific papers and publications, but I do believe I have captured the main points within. So in summary , here is a list of some key take outs regarding the retention of muscle mass, which must include the following:

-

Stay active. This is the single most important target for anyone who wishes to benefit from a longer life and a healthier one.

-

Perform some resistance exercise at least three times per week. This is the silver bullet of slowing down the loss of muscle mass.

-

Ensure you have a protein intake of at least 1.2grams per kg per day. This means a protein intake of at least 90 grams for a 75kg person, both male and female.

-

Consider supplementing with a daily protein drink each day and if you can take this at breakfast, then this will help you even better than taking it late in the evening. Any protein source is acceptable, though the data tells us that whey protein has the edge over all others. If you can find a shake which also includes HMB too, then you will have the perfect drink for maintaining muscle.

-

Eat oily fish at least twice a week to get all the necessary omega 3 fats into your diet. If you are not a fan of fish, then simply take a daily dose of a high-quality omega 3 fish oil supplement.

-

Consider taking a daily supplement containing vitamin D, C, magnesium, selenium and calcium

-

Exercise will help with your energy levels but getting a good nights sleep(preferably eight hours) combined with a daily B vitamin complex will also ensure that you are doing everything you can to stay energised and fight fatigue.